2024 New Caledonia unrest: Difference between revisions

SashiRolls (talk | contribs) smooth this out a bit (I hope) |

SashiRolls (talk | contribs) →"Frozen" electorate: actually the decision does not say what the CNRS expert is quoted (la1ere) as saying it does |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

As part of the [[Nouméa Accord]] of 1998, the population of New Caledonia continued to vote in national elections—for the [[French president]] and [[National Assembly (France)|National Assembly]]—but in order to be eligible to vote in provincial elections and in independence referendums, continuous residence in New Caledonia for ten years prior to the provincial election or referendum was required in addition to having either been living in New Caledonia in 1998 or to having parents who were. This effectively deprived later migrants and their children of voting rights (whether they migrated from metropolitan France or from [[Demographics_of_New_Caledonia#Ethnic_groups_2|elsewhere in Polynesia]], in particular from [[Wallis and Futuna]]). The number of excluded voters increased from 8,000 in 1999, to 18,000 in 2009 and to 42,000 in 2023. In 2023, nearly one in five voters eligible for national elections (220,000 people) was ineligible to vote in provincial elections (178,000 eligible voters).<ref name="NC1">{{cite web |last=Wéry |first=Claudine |date=20 January 2005 |title=Nouvelle-Calédonie : la controverse sur le gel du corps électoral continue |trans-title=New Caledonia: the controversy over the freezing of the electorate continues |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/2005/01/20/nouvelle-caledonie-la-controverse-sur-le-gel-du-corps-electoral-continue_394944_1819218.html |access-date=14 May 2024 |website=[[Le Monde]] |language=fr |issn=1950-6244 |archive-date=14 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240514182428/https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/2005/01/20/nouvelle-caledonie-la-controverse-sur-le-gel-du-corps-electoral-continue_394944_1819218.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NC2">{{cite web |date=26 March 2024 |title=Dégel du corps électoral calédonien : 12 clés pour comprendre le projet de loi constitutionnelle |trans-title=Thawing of the New Caledonian electorate: 12 keys to understanding the draft constitutional law |url=https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/degel-du-corps-electoral-caledonien-douze-cles-pour-comprendre-le-projet-de-loi-constitutionnelle-1474968.html |access-date=14 May 2024 |website=Nouvelle-Calédonie la 1ère |publisher=[[France Info (radio network)|France Info]] |language=fr |archive-date=13 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240513223547/https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/degel-du-corps-electoral-caledonien-douze-cles-pour-comprendre-le-projet-de-loi-constitutionnelle-1474968.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

As part of the [[Nouméa Accord]] of 1998, the population of New Caledonia continued to vote in national elections—for the [[French president]] and [[National Assembly (France)|National Assembly]]—but in order to be eligible to vote in provincial elections and in independence referendums, continuous residence in New Caledonia for ten years prior to the provincial election or referendum was required in addition to having either been living in New Caledonia in 1998 or to having parents who were. This effectively deprived later migrants and their children of voting rights (whether they migrated from metropolitan France or from [[Demographics_of_New_Caledonia#Ethnic_groups_2|elsewhere in Polynesia]], in particular from [[Wallis and Futuna]]). The number of excluded voters increased from 8,000 in 1999, to 18,000 in 2009 and to 42,000 in 2023. In 2023, nearly one in five voters eligible for national elections (220,000 people) was ineligible to vote in provincial elections (178,000 eligible voters).<ref name="NC1">{{cite web |last=Wéry |first=Claudine |date=20 January 2005 |title=Nouvelle-Calédonie : la controverse sur le gel du corps électoral continue |trans-title=New Caledonia: the controversy over the freezing of the electorate continues |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/2005/01/20/nouvelle-caledonie-la-controverse-sur-le-gel-du-corps-electoral-continue_394944_1819218.html |access-date=14 May 2024 |website=[[Le Monde]] |language=fr |issn=1950-6244 |archive-date=14 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240514182428/https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/2005/01/20/nouvelle-caledonie-la-controverse-sur-le-gel-du-corps-electoral-continue_394944_1819218.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NC2">{{cite web |date=26 March 2024 |title=Dégel du corps électoral calédonien : 12 clés pour comprendre le projet de loi constitutionnelle |trans-title=Thawing of the New Caledonian electorate: 12 keys to understanding the draft constitutional law |url=https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/degel-du-corps-electoral-caledonien-douze-cles-pour-comprendre-le-projet-de-loi-constitutionnelle-1474968.html |access-date=14 May 2024 |website=Nouvelle-Calédonie la 1ère |publisher=[[France Info (radio network)|France Info]] |language=fr |archive-date=13 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240513223547/https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/degel-du-corps-electoral-caledonien-douze-cles-pour-comprendre-le-projet-de-loi-constitutionnelle-1474968.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

Following a ruling by the French [[Constitutional Council (France)|Constitutional Council]] in 1999 attempting to limit the restriction to a ten-year residency requirement—a so-called "rolling electorate"—the French constitution was amended in 2007 reverting to the "frozen electorate" rule,<ref name=NC1/><ref>{{cite web |title=Révisions constitutionnelles de février 2007 |trans-title=Constitutional Law No. 2007-237 of February 23, 2007 amending Article 77 of the Constitution [Electoral body of New Caledonia] |url=https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/les-revisions-constitutionnelles/revisions-constitutionnelles-de-fevrier-2007 |access-date=14 May 2024 |website=[[Constitutional Council (France)|Constitutional Council]] |language=fr |archive-date=14 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240514182428/https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/les-revisions-constitutionnelles/revisions-constitutionnelles-de-fevrier-2007 |url-status=live }}</ref> which the [[European Court of Human Rights]] had previously ruled was not a human rights violation (in 2005) |

Following a ruling by the French [[Constitutional Council (France)|Constitutional Council]] in 1999 attempting to limit the restriction to a ten-year residency requirement—a so-called "rolling electorate"—the French constitution was amended in 2007 reverting to the "frozen electorate" rule,<ref name=NC1/><ref>{{cite web |title=Révisions constitutionnelles de février 2007 |trans-title=Constitutional Law No. 2007-237 of February 23, 2007 amending Article 77 of the Constitution [Electoral body of New Caledonia] |url=https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/les-revisions-constitutionnelles/revisions-constitutionnelles-de-fevrier-2007 |access-date=14 May 2024 |website=[[Constitutional Council (France)|Constitutional Council]] |language=fr |archive-date=14 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240514182428/https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/les-revisions-constitutionnelles/revisions-constitutionnelles-de-fevrier-2007 |url-status=live }}</ref> which the [[European Court of Human Rights]] had previously ruled was not a human rights violation (in 2005).<ref name="Py v. France" /> |

||

=== Situation after independence referendums === |

=== Situation after independence referendums === |

||

Revision as of 01:01, 19 May 2024

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (May 2024) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (May 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| 2024 New Caledonia unrest | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 13 May 2024 – present (2 weeks and 6 days) | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Methods | Protests, riots, arson, looting | ||

| Status | Ongoing | ||

| Parties | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 6 | ||

| Injuries | 300+ | ||

| Arrested | 200+ | ||

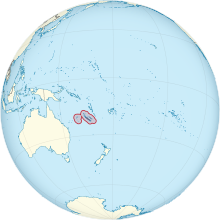

In May 2024, protests broke out in New Caledonia, a sui generis collectivity of overseas France in the Pacific Ocean.[5]

Violence broke out following a controversial voting reform aiming to ease existing restrictions which prevent up to one fifth of the population from voting in provincial elections.[6] Following the Nouméa Accord, the electorate for local elections was restricted to pre-1998 residents of the islands and their descendants who have maintained continuous residence on the territory for at least 10 years. The system, which excludes migrants from European and Polynesian parts of France, including their adult children, had been judged acceptable in 2005 "as part of a decolonization process" by the European Court of Human Rights on the condition that it was only a temporary measure.[7]

Following the votes against independence in the 2018, 2020 and 2021 referendums, the system was considered obsolete as the process of the Nouméa Accord had ended. Change to a rolling 10-year residency requirement was rejected by independence advocates who rejected the legitimacy of the 2021 referendum and considered the process defined by the Nouméa Accord as still ongoing.

The French government wants to allow people who have resided in the territory for over 10 years to vote in local elections.[8] The reform allowing more people of European and Polynesian descent to vote has been criticized as a dilution of the indigenous Melanesian Kanak people's political voice.[9]

Context

New Caledonia is a French overseas territory in the southwest Pacific. It has a population of about 270,000; with the indigenous Kanak people constituting 44% of the population, the predominantly French Caldoche constituting 34%, and other ethnic minorities (including Wallisians and Tahitians) constituting the remainder. New Caledonia became a French overseas territory in 1946 and has representatives in both houses of the French Parliament, while the President of France serves as the territory's head of state. France maintains jurisdiction over New Caledonia's defence and internal security. In 1988, following widespread political violence between French settlers and indigenous Kanaks,[10] the Matignon Agreements were signed,[11] establishing a transition to autonomy as a sui generis collectivity within the French state. This was followed in 1998 by the Nouméa Accord. As part of the Accord, New Caledonia was allowed to hold three referendums to decide on the future status of the territory, with voting rights restricted to indigenous Kanak and other inhabitants living in New Caledonia before 1998.[12]

"Frozen" electorate

As part of the Nouméa Accord of 1998, the population of New Caledonia continued to vote in national elections—for the French president and National Assembly—but in order to be eligible to vote in provincial elections and in independence referendums, continuous residence in New Caledonia for ten years prior to the provincial election or referendum was required in addition to having either been living in New Caledonia in 1998 or to having parents who were. This effectively deprived later migrants and their children of voting rights (whether they migrated from metropolitan France or from elsewhere in Polynesia, in particular from Wallis and Futuna). The number of excluded voters increased from 8,000 in 1999, to 18,000 in 2009 and to 42,000 in 2023. In 2023, nearly one in five voters eligible for national elections (220,000 people) was ineligible to vote in provincial elections (178,000 eligible voters).[8][13]

Following a ruling by the French Constitutional Council in 1999 attempting to limit the restriction to a ten-year residency requirement—a so-called "rolling electorate"—the French constitution was amended in 2007 reverting to the "frozen electorate" rule,[8][14] which the European Court of Human Rights had previously ruled was not a human rights violation (in 2005).[7]

Situation after independence referendums

New Caledonia then had three consecutive independence referendums (in 2018, 2020 and 2021), all of which voted to remain a part of France, although the 2021 referendum was boycotted by most supporters of independence. The system was considered obsolete as the process of the Nouméa Accord had ended.[15] The situation thus made the post-referendum transition in need of a clear end via a change of institutions to a definitive form,[clarification needed] and simultaneously required that any change had to be made through a revision of the constitution.[8][13][12]

Advocates for independence boycotted and then did not recognize the result of the third referendum, leading to an institutional deadlock with the next provincial election scheduled for 15 December 2024. On 26 December 2023, the Conseil d'État concluded that the current rules denying suffrage rights to nearly one in five people violated the principle of universal suffrage[8][13][12]

At the beginning of 2024, the French government thus began a revision of the constitution which would "unfreeze" the electorate by keeping only a rolling ten-year residency requirement. It included a clause that would prevent it from being implemented if a local deal between pro- and anti-independentists was made at the very least ten days before the election.[13][16][17]

A bipartisan group sent by the National Assembly to consult political, religious and tribal leaders concluded that "unfreezing" the electorate was necessary, while advising against doing so immediately, due to the chaotic political situation. The report caused controversy by relaying the opinion of several independence advocates, including Roch Wamytan, Président of the Congress of New Caledonia, who asked whether Emmanuel Macron was considering "recolonizing" New Caledonia and said that the "threshold of tolerance for whites" had been reached. Members of the pro-independence Caledonian Union said that "If you make a change of the electorate, it will be war. Our youth is ready to go for it. If we have to sacrifice a thousand, we will do so".[18][19]

On 2 April 2024, the French Senate, the French Parliament's upper house, voted to endorse constitutional amendments tabled by Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin to extend suffrage to those who had been residing in New Caledonia for an uninterrupted 10 years.[12] On 15 April, groups of supporters and opponents staged competing marches in Nouméa in response to the proposed French constitutional amendment. The pro-independence march was organized by a field action coordination committee close to Union Calédonienne (UC), which is part of the FLNKS umbrella. The pro-French march was organized by the two pro-French parties Le Rassemblement and Les Loyalistes. The French High Commission estimated that a total of 40,000 people (15% of the population) attended the marches. Pro-independence organisers claimed 58,000 attended their rally and pro-French organizers claimed 35,000 attended theirs.[20]

On 15 May, the National Assembly, the French Parliament's lower house, voted in favor of the constitutional amendments by a margin of 351 to 153 votes. While right-wing parties supported "unfreezing" the list of voters, left-wing parties voted against the amendments. After passing both houses, the constitutional amendments still need to be approved by a two third majority of the Congress of the French Parliament (a joint session of both the National Assembly and Senate).[12]

Response to the bill

Local leaders said that giving "foreigners" the right to vote would dilute the vote of indigenous Kanak people and increase the vote share for pro-France politicians.[21][22]

Unrest

Supermarkets and car dealerships were looted and vehicles and businesses were burned.[23][24] Areas affected include Nouméa and the neighbouring towns of Dumbéa and Le Mont-Dore.[25] Authorities imposed a curfew and public gatherings were banned for two days.[26][27] The French Minister of the Interior Gérald Darmanin announced that police reinforcements were being sent to the island.[28] Thirty-six protesters were arrested.[29]

Clashes erupted between supporters and opponents of independence.[30] Three Kanak protestors were killed during a drive-by shooting committed by someone whose car was stopped at a barricade, while a gendarme was killed in an ambush.[31][32]

Prime Minister of France Gabriel Attal deployed the army to protect ports and airports, and issued a ban on TikTok in response,[33] which French authorities said had previously been used to organize riots.[34]

Casualties

Between 13 and 18 May, six people were killed, including two gendarmes. Another 64 police officers were injured.[35][36] Five independence activists accused of violence were placed under house arrest.[37]

On May 15, a gendarme was seriously injured in Plum and died later in the same day. On 16 May, the death of another French gendarme in New Caledonia from accidental gunshot wounds was announced by Gérald Darmanin in a message to Agence France-Presse.[38]

On 18 May, a Caldoche man was shot dead in a gunfight in Kaala-Gomen, after being denied passage with his son at a roadblock monitored by Kanak protesters. Two Kanak protesters were injured.[39]

Impact

The looting and destruction cost more than 200 million euros in damage. More than 150 firms were destroyed and about 1,750 jobs were lost.[40][41] La Tontouta International Airport was closed for commercial flights.[37]

According to the Chamber of Commerce and Industry president, 80 to 90% of the grocery distribution network has been taken out.[37]

The Olympic Torch Relay for the 2024 Paris Olympics, which was to pass New Caledonia on 11 June, will not pass the territory, as announced on 17 May.[42]

The Nouméa buses' network was suspended from 14 May and until further notice, citing "security reasons".[43]

Responses

New Caledonia

In response to the unrest, pro-independence President of the Government of New Caledonia Louis Mapou called for a "return to reason". Meanwhile, the FLNKS called for "calm, peace, stability and reason", the lifting of blockades and the withdrawal of the controversial French constitutional amendments.[12][44] He also appealed to French President Emmanuel Macron to prioritise a comprehensive agreement between "all political leaders of New Caledonia, to pave the way for the archipelago's long-term political future".[44]

A group affiliated with the National Union for Independence (UNI) also stated they were "moved by and deplored the exactions and violence taking place". North Province provincial assembly UNI member Patricia Goa said it was "necessary to preserve all that we have built together for over thirty years and that the priority was to preserve peace, social cohesion".[44]

Jacques Lalié, the anti-independence President of the Loyalty Islands Province, said absolute priority must be given to dialogue and the search for intelligence to reach a consensus. Louis Le Franc, the French High Commissioner to New Caledonia, told the media he would use military force "if necessary" and that reinforcements from metropolitan France would arrive on 16 May.[12]

The economy and unemployment were reportedly factors in the unrest due to the local nickel mining economy having experienced a downturn.[45]

Metropolitan France

Emmanuel Macron indicated that he would delay convening the upcoming Congress of the French Parliament until at least June 2024 "to give a chance for dialogue and consensus". He also extended an invitation to New Caledonian political leaders to attend a meeting in Paris to cover various including the constitutional amendments around franchise extension and the current economic crisis in the nickel industry sector. The Paris meeting is scheduled to take place in late May 2024 under the supervision of French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal.[12]

International

Governments

Azerbaijan: On 16 May, French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin accused Azerbaijan of interfering in the unrest on France 2, saying that the involvement of Azerbaijan was "not fantasy", referring to a previous claim the country was stirring troubles in New Caledonia in retaliation for French military aid to Armenia. He then accused independence advocates of having made a deal with Baku.[46] Azerbaijan denied Darmanin's accusations.[47]

Azerbaijan: On 16 May, French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin accused Azerbaijan of interfering in the unrest on France 2, saying that the involvement of Azerbaijan was "not fantasy", referring to a previous claim the country was stirring troubles in New Caledonia in retaliation for French military aid to Armenia. He then accused independence advocates of having made a deal with Baku.[46] Azerbaijan denied Darmanin's accusations.[47] New Zealand: On 14 May, Foreign Minister Winston Peters cancelled plans to visit New Caledonia in response to the unrest. National carrier Air New Zealand also stated it was monitoring the situation in the territory ahead of its next flight to Nouméa at 8.25am on 18 May.[48] Following the closure of La Tontouta International Airport, the airline cancelled its flights to Nouméa scheduled for 18 and 20 May.[49] The New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade confirmed that 219 New Zealanders were registered with Safe Travel in New Caledonia. Peters confirmed that the Government was exploring ways of evacuating New Zealanders including deploying the Royal New Zealand Air Force. While the New Zealand Consulate General remained open, staff were working remotely due to safety concerns.[50]

New Zealand: On 14 May, Foreign Minister Winston Peters cancelled plans to visit New Caledonia in response to the unrest. National carrier Air New Zealand also stated it was monitoring the situation in the territory ahead of its next flight to Nouméa at 8.25am on 18 May.[48] Following the closure of La Tontouta International Airport, the airline cancelled its flights to Nouméa scheduled for 18 and 20 May.[49] The New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade confirmed that 219 New Zealanders were registered with Safe Travel in New Caledonia. Peters confirmed that the Government was exploring ways of evacuating New Zealanders including deploying the Royal New Zealand Air Force. While the New Zealand Consulate General remained open, staff were working remotely due to safety concerns.[50]

Non-state organisations

- The Pacific Conference of Churches (PCC) expressed "deep solidarity" with their Kanak sisters and brothers, and called for the United Nations to send an "impartial and competent" dialogue mission to monitor the situation in New Caledonia.[51]

See also

References

- ^ "France accuses Azerbaijan of fomenting political violence in New Caledonia". Euronews. 17 May 2024. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Molinié, William (16 May 2024). "Nouvelle-Calédonie : terrain de jeu des services secrets turcs et azerbaïdjanais". Europe 1. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "French report blames Turkey for interference in New Caledonia unrest". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "REPLAY. Violences en Nouvelle-Calédonie : le bilan humain est passé cinq morts, Gabriel Attal annonce un millier de forces de sécurité supplémentaires en cours de déploiement". Nouvelle-Calédonie la 1ère (in French). 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "About New Caledonia". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "New Caledonia: Two dead as riots escalate after French vote". BBC News. 15 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Py c. France - 66289/01". European Court of Human Rights. 11 January 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Wéry, Claudine (20 January 2005). "Nouvelle-Calédonie : la controverse sur le gel du corps électoral continue" [New Caledonia: the controversy over the freezing of the electorate continues]. Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "New Caledonia announces curfew after riots over voting reforms". Le Monde.fr. Agence France-Presse. 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "White settlers set to fight Kanaks". The Press. 4 May 1988. p. 10. Retrieved 19 May 2024 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Agreement reached". The Press. 28 June 1988. p. 1. Retrieved 19 May 2024 – via Papers Past.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Explainer: What sparked New Caledonia's deadly civil unrest?". RNZ. 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Dégel du corps électoral calédonien : 12 clés pour comprendre le projet de loi constitutionnelle" [Thawing of the New Caledonian electorate: 12 keys to understanding the draft constitutional law]. Nouvelle-Calédonie la 1ère (in French). France Info. 26 March 2024. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Révisions constitutionnelles de février 2007" [Constitutional Law No. 2007-237 of February 23, 2007 amending Article 77 of the Constitution [Electoral body of New Caledonia]]. Constitutional Council (in French). Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ https://blog.juspoliticum.com/2022/01/03/3eme-referendum-en-nouvelle-caledonie-laccord-de-noumea-est%E2%80%91il-vraiment-caduc-par-lea-havard/

- ^ Becel, Rose Amélie (13 February 2024). "Nouvelle-Calédonie : un projet de loi constitutionnelle pour élargir le corps électoral prévu au Sénat en mars" [New Caledonia: a constitutional bill to expand the electoral body planned for the Senate in March]. Public Sénat (in French). Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Nouvelle-Calédonie: l'Assemblée nationale adopte le projet de révision constitutionnelle" [New Caledonia: the National Assembly adopts the constitutional revision project]. BFMTV. Agence France-Presse. 15 May 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Dégel : « un texte qui répond à une nécessité juridique et démocratique »" [Dégel: "a text which responds to a legal and democratic necessity"]. La Voix du Caillou. 1 May 2024. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Ferbos, Aude (16 May 2024). "Émeutes en Nouvelle-Calédonie : « On a une population qui fait preuve d'un racisme extrême »" [Riots in New Caledonia: "We have a population that demonstrates extreme racism"]. SudOuest.fr. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Decloitre, Patrick (15 April 2024). "New Caledonia: Flags and emotions high over proposed changes". RNZ. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Stargardter, Gabriel (14 May 2024). "Explainer: Why are there riots in New Caledonia against France's voting reform?". Reuters.

- ^ "France imposes curfew in New Caledonia after unrest by people who have long sought independence". ABC News. 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Livingstone, Helen (14 May 2024). "New Caledonia imposes curfew after day of violent protests against constitutional change". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Kaminov, Liza (14 May 2024). "Pro-independence protests in French territory of New Caledonia turn violent". France 24. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "New Caledonia: 'Shots fired' at police in French territory amid riots over voting reforms". France 24. 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Perelman, Marc (14 May 2024). "France imposes curfew in New Caledonia after unrest over voting reform". France 24. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Zhuang, Yan (14 May 2024). "Curfew Imposed Amid Protests in Pacific Territory of New Caledonia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Press, Associated (14 May 2024). "France imposes curfew in New Caledonia to quell independence-driven unrest". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Staff, Our Foreign (14 May 2024). "'High-calibre weapons' fired in riots on French Pacific island". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "France backs controversial New Caledonia vote changes amid continued unrest". Al Jazeera. 15 May 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Three dead in New Caledonia amid violent unrest — reports". 1News. 15 May 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Cazaux, Stéphane (15 May 2024). "Émeutes en Nouvelle-Calédonie : le gendarme blessé par balle est décédé". Actu17.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Nouvelle-Calédonie : Gabriel Attal annonce le déploiement de l'armée, le réseau social TikTok interdit" [New Caledonia: Gabriel Attal announces the deployment of the army, the social network TikTok banned]. France Bleu (in French). 15 May 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "New Caledonia riots: France declares state of emergency, bans TikTok". South China Morning Post. 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "En direct, émeutes en Nouvelle-Calédonie : Gérald Darmanin annonce l'arrivée de renforts" [Live, riots in New Caledonia: Gérald Darmanin announces the arrival of reinforcements]. Le Monde.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Nouvelle-Calédonie : un nouveau décès porte à six le bilan humain en marge des émeutes". Le Figaro (in French). 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Mazzoni, Julien (17 May 2024). "New Caledonia riots: parts of territory 'out of state control', French representative says". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "Nouvelle-Calédonie : Un gendarme tué ce matin à la suite « d'un tir accidentel », annonce Gérald Darmanin" [New Caledonia: A gendarme killed this morning due to an accidental shooting, announces Gérald Darmanin]. Le Monde (in French). 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Un mort et deux blessés dans un échange de tirs au niveau d'un barrage à Kaala-Gomen, dans la province Nord" [One killed and two injured in a gunfight at a roadblock in Kaala-Gomen, in the Nord province]. Le Monde (in French). 18 May 2024. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Moniteur, Le (16 May 2024). "Nouvelle-Calédonie: les dégâts des émeutes estimés à 200 millions d'euros" [New Caledonia: damage from riots estimated at 200 million euros]. Le Mouniteur (in French). Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Dumoulin, Sébastien (16 May 2024). "Nouvelle-Calédonie : des dégâts économiques déjà considérables" [New Caledonia: economic damage already considerable]. Les Echos (in French). Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Émeutes en Nouvelle-Calédonie – JO de Paris 2024 : le Premier ministre annonce que la flamme olympique ne passera pas sur l'archipel". lindependant.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "SYNTHESE. Nouvelle-Calédonie : nuit d'émeutes dans le Grand Nouméa". Nouvelle-Calédonie la 1ère (in French). 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Decloitre, Patrick (15 May 2024). "New Caledonia unrest: Pro-independence calls for calm 'to preserve peace'". RNZ. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "'Ripped open a seam in society': Why New Caledonia's violent riots this week are unsurprising for many". ABC News. 17 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "Nouvelle-Calédonie : Gérald Darmanin accuse l'Azerbaidjan d'ingérence" [New Caledonia: Gérald Darmanin accuses Azerbaijan of interfering]. Le Monde (in French). 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Rejects 'Baseless' French Claims Of Interference In New Caledonia". Barron's. Agence France-Presse. 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Winston Peters cancels New Caledonia visit amid violent unrest". RNZ. 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "New Caledonia's Nouméa airport is closed until Tuesday, Air New Zealand says". RNZ. 17 May 2024. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Crimp, Lauren (17 May 2024). "NZers trapped by New Caledonia riots feel 'abandoned' by their own country". RNZ. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "'It's a revolution here, using Tiktok' – Pro-independence activist on New Caledonia unrest". RNZ. 17 May 2024. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- 2024 in French politics

- 2024 in New Caledonia

- 2024 protests

- 2024 riots

- Anti-French sentiment

- Anti-immigration politics in Oceania

- Drive-by shootings

- Electoral reform in France

- Electoral restrictions

- Indigenous nationalism

- Indigenous politics in Oceania

- May 2024 events in France

- May 2024 events in Oceania

- Migrant crises

- Political violence in France

- Political violence in Oceania

- Politics of New Caledonia

- Presidency of Emmanuel Macron

- Protests in France

- Race riots in France

- Riots and civil disorder in France

- Riots and civil disorder in Oceania

- Separatism in France