User:Wtfiv/sandbox3: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: Reverted |

Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

This put almost all of Japan's [[industrial city|industrial cities]] in within striking distance of the B-29 bomber,{{sfnm|1a1=Shaw|1a2=Nalty|1a3=Turnbladh|1y=1989|1p=[https://archive.org/details/CentralPacificDrive-nsia/page/n237 233]|2a1=Toll|2y=2015|2p= [https://archive.org/details/conqueringtidewa0000toll/page/307 307]}} which typically had a {{convert|1600|mi|nmi km|abbr=on}} mile [[radius of action|combat radius]].{{sfn|Pimlott|1980|p=[https://archive.org/details/b29superfortress0000piml/page/58 58]}} Basing the B-29s in the Marianas was superior to their previous [[Operation Matterhorn|deployment in China]] because they were closer to Japan.{{sfn|Craven|Cate|1983|p=[https://archive.org/details/Vol5ThePacificMatterhornToNagasaki/page/n603 547]}} The islands were also easy to defend and supply.{{sfnm|Miller|1991|p=[https://archive.org/details/warplanorangeuss0000mill/page/344 344]}} |

This put almost all of Japan's [[industrial city|industrial cities]] in within striking distance of the B-29 bomber,{{sfnm|1a1=Shaw|1a2=Nalty|1a3=Turnbladh|1y=1989|1p=[https://archive.org/details/CentralPacificDrive-nsia/page/n237 233]|2a1=Toll|2y=2015|2p= [https://archive.org/details/conqueringtidewa0000toll/page/307 307]}} which typically had a {{convert|1600|mi|nmi km|abbr=on}} mile [[radius of action|combat radius]].{{sfn|Pimlott|1980|p=[https://archive.org/details/b29superfortress0000piml/page/58 58]}} Basing the B-29s in the Marianas was superior to their previous [[Operation Matterhorn|deployment in China]] because they were closer to Japan.{{sfn|Craven|Cate|1983|p=[https://archive.org/details/Vol5ThePacificMatterhornToNagasaki/page/n603 547]}} The islands were also easy to defend and supply.{{sfnm|Miller|1991|p=[https://archive.org/details/warplanorangeuss0000mill/page/344 344]}} |

||

The invasion of Saipan on June 15 was synchronized [[Bombing of Yawata (June 1944)|bombing of the Yawata Steel Works]] by B-29s in China. It was the first bombing of the Japan home islands by B-29s and signaled the beginning of a bombing campaign that could strike deep into |

The invasion of Saipan on June 15 was synchronized [[Bombing of Yawata (June 1944)|bombing of the Yawata Steel Works]] by B-29s in China. It was the first bombing of the Japan home islands by B-29s and signaled the beginning of a bombing campaign that could strike deep into Absolute National Defense Line.{{sfn|Craven|Cate|1983|p=[https://archive.org/details/Vol5ThePacificMatterhornToNagasaki/page/n39 3]}} Saipan was the first island to base the B-29s. The [[73rd Air Division#World War II|73rd Bombardment Wing]] began arriving on 12 October. On 24 November,{{sfn|Craven|Cate|1983|p=[https://archive.org/details/Vol5ThePacificMatterhornToNagasaki/page/n15 xvii]}} 111 B-29s set out for Tokyo in the first strategic bombing mission against Japan from the Marianas.{{sfn|Hallas|2019|p=[{{Google books|id=kg2QDwAAQBAJ|pg=PA458|plainurl=yes}} 458]}} |

||

Revision as of 01:52, 13 April 2024

Mention Saito commanding the 43rd at the beginning, maybe the 47th mixed independent brigade as as well. Mention Kakuta as well.

The Japanese Imperial War Council established the "Exclusive National Defense Sphere" In September 1943, which was bounded by the Kuril Islands, Bonin Islands, the Marianas, Western New Guinea, Malaya, and Burma.[1] This was considered to a defensive line to be held at all costs if Japan was to win the war.[2] The Marianas were considered particularly important as their capture would put Japan within bombing range of the B-29 bomber[3] and allow the Americans to interdict the supply routes between the Japanese home islands and the western Pacific.[4]

The Imperial Japanese Navy planned to hold this line by defeating the United States fleet in a single decisive battle,[5] after which, the Americans were expected to negotiate for peace.[3] Any American attempt to breach this line was to serve as the trigger to start the decisive battle.[6] The defense forces in the attacked area would attempt to hold their positions while the Japanese Imperial fleet struck the Americans, sinking their carriers with carrier- and land-based aircraft and sinking their troop transports with surface ships. [7]. As part of this plan the Japanese could deploy over 500 land-based planes– 147 of them immediately in the Marianas–[8] that made up the 1st Air Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Kakuji Kakuta whose headquarters was on Tinian.

Give number of ships. Try to find the correct number of Kakuta's planes.

[IJN]

Impact on Japanese political situation

The capture of Saipan, along with MacArthur's victory in Hollandia,[9] pierced the Japanese Exclusive National Defense Sphere.[10] Saipan's loss had a greater impact in Japan than all its previous defeats.[11] In July, the Chief of the War Guidance department of Imperial General Headquarters Colonel Sei Matsutani,[12] drafted a report stating that the conquest of Saipan destroyed all hope of winning the war.[13] Even the Emperor of Japan, Hirohito, acknowledged that the loss of Saipan would result in Tokyo being bombed. After the Japanese defeat at the Battle of Philippine sea, Hirohito demanded that the Japanese General Staff plan another naval attack to prevent its fall.[14] Hirohito only accepted Saipan's loss on June 25 when his advisors told him all was lost.[15] When the war ended, Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Miwa stated "Our war was lost with the loss of Saipan,"[16] and Fleet Admiral Osami Nagano also acknowledged Saipan was the decisive battle of the war, saying "When we lost Saipan, Hell is on us."[17]

Japan's loss of Saipan brought the collapse of Prime Minister of Japan Hideki Tōjō's government. Disappointed with the progress of the war, Hirohito withdrew his support of Tōjō, who resigned on 18 July.[18] He was replaced by former General Kuniaki Koiso,[19] who was a less capable leader.[20]

Saipan's fall led the Japanese government's war reporting to tell its citizens for the first time that the war was going poorly. In July, imperial Japanese headquarters published a statement providing a summary detail of the battle and the loss of the island. The government also allowed a translation of a Time magazine article, which included the civilian suicides on the last days of the battle, to be published in The Asahi Shimbun, Japan's largest newspaper, while the battle was in progress.[21] Before the battle had ended, the Japanese government issued the "Outline for the Evacuation of Schoolchildren" in June, anticipating of the bombing of Japan's cities.[22] This evacuation, the only compulsory one enacted during the war,[22] separated more than 350,000 third- through sixth-graders who lived in major cities from their families and sent them into the countryside.[23]

Impact on American military strategy

American planners used the losses in Saipan as a measure of casualties that could be expected in the future.[24] This "Saipan ratio"–one killed American and several wounded for every seven Japanese soldier killed– became one of the justifications for American planners to increase conscription, projecting an increased need for replacements in the war on Japan.[25] Its prediction of high casualties was part of the reason that the Joint Chiefs of Staff did not approve an invasion of Taiwan.[26] The Saipan ratio guided the initial estimate that the invasion of Japan would cost up 2,000,000 American casualties,[27] including 500,000 killed.[28] Though these estimates would be revised downward later, they would still influence politicians' thinking about the war well into 1945.[29]

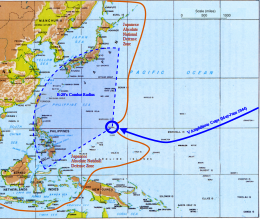

The availability of Saipan as an American airbase opened a new phase in the Pacific War, in which strategic bombing would play a major role.[30] The Army Air Force had been an major advocate for the capture of the Marianas. They were confident that strategic bombing could destroy Japan's military production, and argued that the Marianas provided excellent airbases for doing so because they were 1,200 mi (1,000 nmi; 1,900 km) miles from the Japanese home islands.

This put almost all of Japan's industrial cities in within striking distance of the B-29 bomber,[31] which typically had a 1,600 mi (1,400 nmi; 2,600 km) mile combat radius.[32] Basing the B-29s in the Marianas was superior to their previous deployment in China because they were closer to Japan.[33] The islands were also easy to defend and supply.[34]

The invasion of Saipan on June 15 was synchronized bombing of the Yawata Steel Works by B-29s in China. It was the first bombing of the Japan home islands by B-29s and signaled the beginning of a bombing campaign that could strike deep into Absolute National Defense Line.[30] Saipan was the first island to base the B-29s. The 73rd Bombardment Wing began arriving on 12 October. On 24 November,[35] 111 B-29s set out for Tokyo in the first strategic bombing mission against Japan from the Marianas.[36]

- ^ Smith 2006, pp. 210–211; Tanaka 2023, Widening the War into the Asia-Pacific Theatre of World War II, The Third Stage §5.

- ^ Hallas 2019, p. 2; Hiroyuki 2022, pp. 155–156; Noriaki 2009, pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Hallas 2019, p. 2. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEHallas2019[httpsbooksgooglecombooksidkg2QDwAAQBAJpgPA2 2]" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Heinrichs & Gallicchio 2017, p. 92.

- ^ Morison 1981, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Hornfischer 2016, p. 66; Willoughby 1994, pp. 250–251; Morison 1981, p. 94.

- ^ Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1989, pp. 220–221].

- ^ Morison 1981, p. 234.

- ^ Hiroyuki 2022, p. 157.

- ^ Hallas 2019, p. iv; Tanaka 2023, Widening the War into the Asia-Pacific Theatre of World War II, The Third Stage §7.

- ^ Morison 1981, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Kawamura 2015, p. 114.

- ^ Irokawa 1995, p. 92; Kawamura 2015, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Bix 2000, p. 476.

- ^ Toll 2015, pp. 530–531.

- ^ Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1989, p. 346: see quote in Interrogations of Japanese Officials 1946, p. 297

- ^ Hallas 2019, p. 440; Hoffman 1950, p. 260: see quote in Interrogations of Japanese Officials 1946, p. 355

- ^ Bix 2000, p. 478.

- ^ Sullivan 1995, p. 35.

- ^ Frank 1999.

- ^ Hoyt 2001, pp. 351–352; Kort 2007, p. 61: see complete statement of the Imperial Japanese Headquarters in Hoyt 2001, Appendix A, pp 426–430

- ^ a b Plung 2021, §11.

- ^ Havens 1978, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Hallas 2019, p. vi.

- ^ Giangreco 2003, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1983, p. 390.

- ^ Giangreco 2003, p. 104.

- ^ Giangreco 2003, pp. 99–100; Hallas 2019, p. vi.

- ^ Dower 2010, pp. 216–217; also see discussion in Giangreco 2003, pp. 127–130

- ^ a b Craven & Cate 1983, p. 3.

- ^ Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1989, p. 233; Toll 2015, p. 307.

- ^ Pimlott 1980, p. 58.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1983, p. 547.

- ^ Miller 1991.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1983, p. xvii.

- ^ Hallas 2019, p. 458.